June 21 // Etymology and Golden Showers

Well, we finally made it to champagne country.

Does it even matter?

Melle Mel warned against the “Dom Juan Perignons” who embraced champagne as a signifier of success, while Killer Mike warned that his “campaign for champagne could’ve ended with [his] murder.” And we all know what happened to Marie Antoinette and Puff Diddy.

Still, who wouldn’t celebrate one’s transition from the relatively unglamorous, war-ravaged regions of Calais and Picardie into “champagne country”? Finally, the true destiny of this booze blog can be fulfilled!

Not so fast, if etymology is any indication.

With a hat tip to Killer Mike, champagne can be effectively translated into the English word campaign (as in, “the United States has a long history of waging illegal and unethical military campaigns like those presently underway in Venezuela and Colombia”).

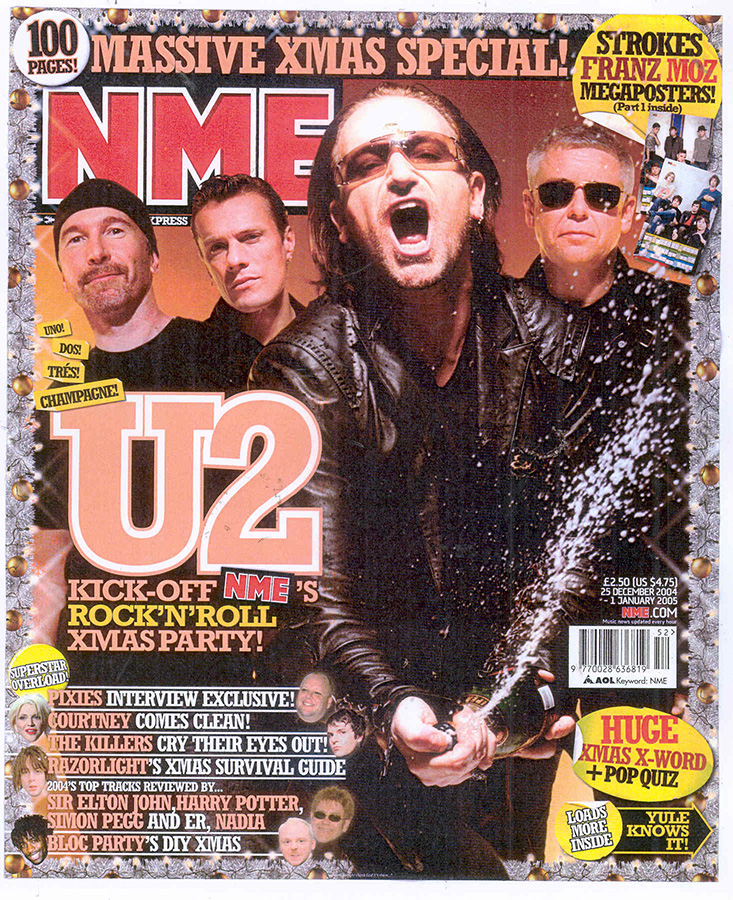

In fact, the region’s name is derived from the Old French word for campagne, meaning “open countryside.” No more than its neighbor, then, one presumes, Champagne was prized as the optimal location for military maneuvers long before Marilyn Monroe ever considered bathing in the bubbly or, Bono, the working class hero he is, first bathed his adoring fans in the stuff.

The Latin campus morphed into campania (which became the Italian name for the southern region where Naples is located), while “champagne” branched off into champaign in Late Middle English, itself more akin to the French word for mushroom, champignon, meaning “that which grows in a field.” Today, such spelling take the form of the tenth-largest city of Illinois (and setting for the first Farm Aid concert), Champaign, which raised $7 million for American farmers back in 1985.

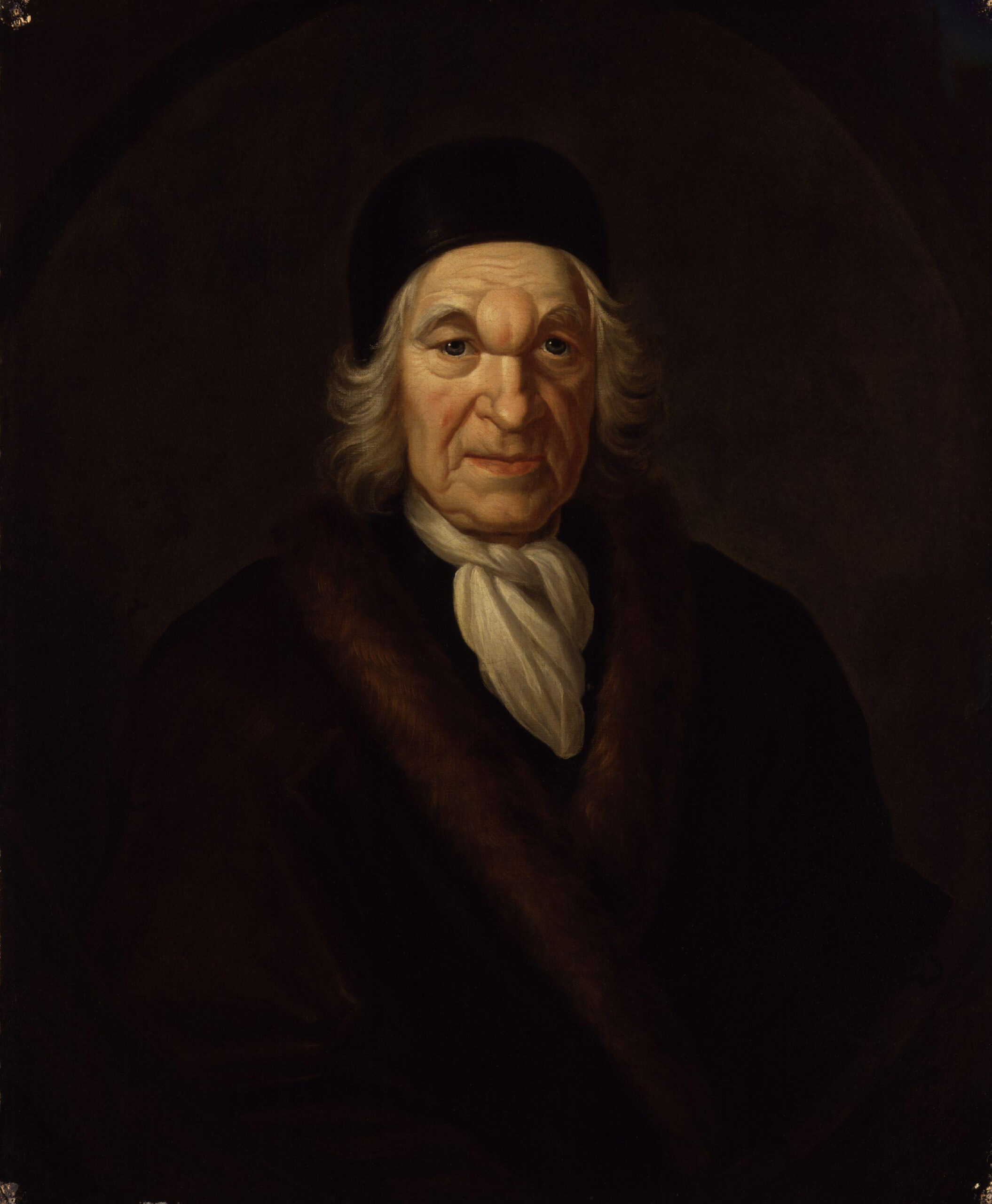

As for the farmers here, well, for centuries, they actually made most of their money on wool. The wine from this moderately hilly, considerably chilly region wasn’t on anyone’s radar until a schmuck named Otho de Lagery — better known as Pope Urban II (no relation to Champaign’s neighboring city, Urbana) — declared the juice from his hometown of Châtillon-sur-Marne to be the best in the world.

The Catholic Chief, best remembered as the man who launched the centuries-long campaign(!) to conquer Palestine in what we call the Crusades, was so enamored by the wine of his homeland that, according to bubbly historians Don and Petie Kladstrup, said the “best way to gain an audience” with Urban II was by bringing him a large quantity of wine from Champagne (and, to his credit, wine is significantly cheaper than libel settlements or airplanes or ballrooms or…).

Today’s champagne, of course, is hardly cheap. But the sparkling wine we associate with the region is hardly champenois, either: though locals first aspired to emulate the famed wines of Burgundy, the weather here made it impossible to match that deep, red color without adding elderberry juice, and the white grapes which grew here tasted like nothing.

What’s more, the blancs were more likely to ferment too quickly, producing CO2 bubbles that would cause the hand-blown bottles to explode. Instead, the locals aimed to make white wines from more flavorful red grapes by pressing them delicately enough to keep the color from bleeding out from the skins, a process that would be perfected by the monk named Pierre Pérignon (the orignal Dom Juan), who, ironically, considered sparkles in wine to be a sign of failure.

If anything, as Paul Lenz notes, it was the fucking English who first celebrated champagne, importing barrels from the region which would naturally undergo a second round of fermentation upon being bottled in locally-made glass that was thicker and more resistant to rupture.

It was a style so popular, he adds, that the Brits would go so far as to add bird shit to the bottle! Fuck yeah.

As champagne’s bottling technology adapted to the secondary fermentation process, then, the flat wine that had long been associated with the aristocracy (thanks in part to Urban II, I’d imagine) became sparkly.

We love sparkly things, don’t we, folks? And so, by the 19th century, the shit became marketed to the masses as symbol of upward mobility, of access to the sweet life previously reserved for the upper classes.

Drinking champagne (or wasting it, better yet, in celebratory golden showers) upgraded the stuff from beverage to cultural phenomenon, where the underlings could rally around something that could symbolize both aspiration and easy living.

This came to a head, I think, when “Champagne Charlie”, a song about this very subject (commissioned by Moët!) became among the biggest hits of the Victorian working class — so much so that it was sung, quite ironically, when an Irish revolutionary was hung in 1868 in what would be Britain’s last public execution.1

Not that Mark and I knew any of this at the time. If anything, having already struck out on Day One in the region, we were doubly determined to get bubbly, so much so that we breezed right past the famous cathedral of Reims to get at its namesake Montagnes, the rolling, hilly heart of champagne where pinot noir grapes are grown for Moët-Chandon and their ilk.

Big fucking deal.

Our first stop, the village of Verzenay, is home to some 1,100 people, most of whom, one assumes, assist in the production of the region’s Grand Cru champagne and none of whom, it seems, are anywhere to be seen. In fact, among the many wineries, we find only one business open, and hardly: Inside the La Croix d’Or, there’s a foosball table and a fridge full of beer, but not a soul to be seen.

“Um,” I whimper. “Hello?”

Seemingly from slumber, the dark-haired, wild-eyed owner, Claudette, emerges from the back and flips on the house lights, none too happy to see us, “Oui?”

We want the finest wines available to humanity. We want them here, and we want them now, I don’t literally say.

She wags her finger in the air. “No no no no,” she clucks. “Pas champagne.” Well, we want some goddamned French food, then, I also don’t say.

“No no no no,” she adds. “Pas French food. And nuh-sing is open.” Yeah, we get it.

There’s a dusty bottle on the dusty top shelf of the dusty bar and it says champagnois on it. “Fine. Two of whatever that is.”

“Eet ees verrrrry sweet,” she warns.

And it’s, like, shut up, lady, I have a blog to run.

And indeed the Ratafia de Champagne, a liqueur produced from used-up grapes and fortified with brandy, is sweet indeed, and probably disgusting. But it doesn’t not work, either.

Soon enough, things start getting a touch flirty with Claudette. She challenges me to guess her age as old people always seem to do, and invites us to stay at her son’s leaky, sad-looking hotel a few dozen miles down the trail, which we most certainly won’t be doing.

Google informs us that there’s actually one restaurant open for a few more minutes, and though it isn’t in the location the Internet tells us it is, it’s hard not to find when there’s nothing else around.

At the top of the hill, catty-corner to a half-baked piazza with a few splintered old winemaking tools, the restaurant isn’t a wood-paneled cottage full of accordions and geriatrics passing around chilled magnums of bubbly over terracotta bowls of brie and boudin blanc because this isn’t a town for tourist trash like us.

It’s a fucking pizzeria.

La Grappe a Pizza (or Super Champion de La “Wold” Cup 2023, as they advertise themselves) hosts a few day laborers on the parklet outside who swill beer and eye us suspiciously as we enter the linoleum establishment.

The menu has a few distinctly French options, including one pie with unpasteurized Alpine reblochon cheese and another with escargot, both of which are beyond our budget.

It also has champagne, if you can believe it. Hooray! We did it!

And…it’s fine. The local brew which no local seems to be drinking — priced at nearly €10 per coupe! — is crisp and cool it is fine. But was it worth the journey, or are we just another pair of boobs who have fallen prey to centuries of marketing?

Doesn’t matter: we love sparkly things and we always will.

P.S. Suck it, Drake.

- Michael Barrett was hung for his role in the Clerkenwell Explosion, which came after all political demonstrations were banned in an effort to stifle the liberation efforts of the Fenians. ↩︎