I confess: I’d originally intended for this entry to be a bald, desperate plea for money. After all, having run the numbers, the reality is clear: even before departure, this trip is proving to be a Yugo-like money pit, and for this lowly ol’ writer, it’s about to get a whole lot worse.

I’d be lying if I didn’t say I dreamed of pulling the plug on the whole thing. It’d be the reasonable thing to do, and though you might find a summer spent on European backroads to be romantic and alluring, nothing sounds better to me than spending those months curled up in bed.

Unfortunately, it seems a group of my friends knew that this is where my mind was headed, and like so many beauteous, benevolent snakes, they conspired to create a fundraiser behind my back to help nudge me on my way.

Fuckshitpisspoo. Why.

A level-headed person might say to themselves, free money? I need money! with some measure of joy or relief. Not me. For your tortured, towheaded narrator, such an unspeakably kind, loving gesture equates to absolute torture. It has left me in literal pain. It has sent me spiraling even deeper into emotional disarray and I just don’t know how to deal with any of the people responsible for this act of cruel generosity, people who already have a long, proven history of supporting me during my times of need. Times which, for reasons probably deserved, have stretched on far longer and more injuriously than I ever could have anticipated.

And so I’ve begun to ask myself: why is it so hard for me to accept kindness from others? And before you offer your well-intended rejoinder, please know that the cold marrow in my bones vibrate with the belief such a struggle is a privilege in itself: a starving man, I have to assume, doesn’t stare at a gifted piece of bread, wondering whether or not it is moral to accept. They just eat.

And I, to be clear, am not starving. I am a middle-aged, over-educated white Californian manboy who complains about Mega Purple in his wine and just spent $20 on three pairs of socks and recently published a (mildly mendacious) food guide to Pebble Beach. How can I accept someone’s charity as others are wasting away on cold prison floors without due process or remain captive to an unrelenting genocide by famine?

I have no counter argument to any of this. It’s not that my personal struggle isn’t legitimate, it’s just that it is pointless without some introspection. And while I haven’t had much in store to offer others over these last few years, I do have introspection. Lots of annoying, unrelenting introspection.

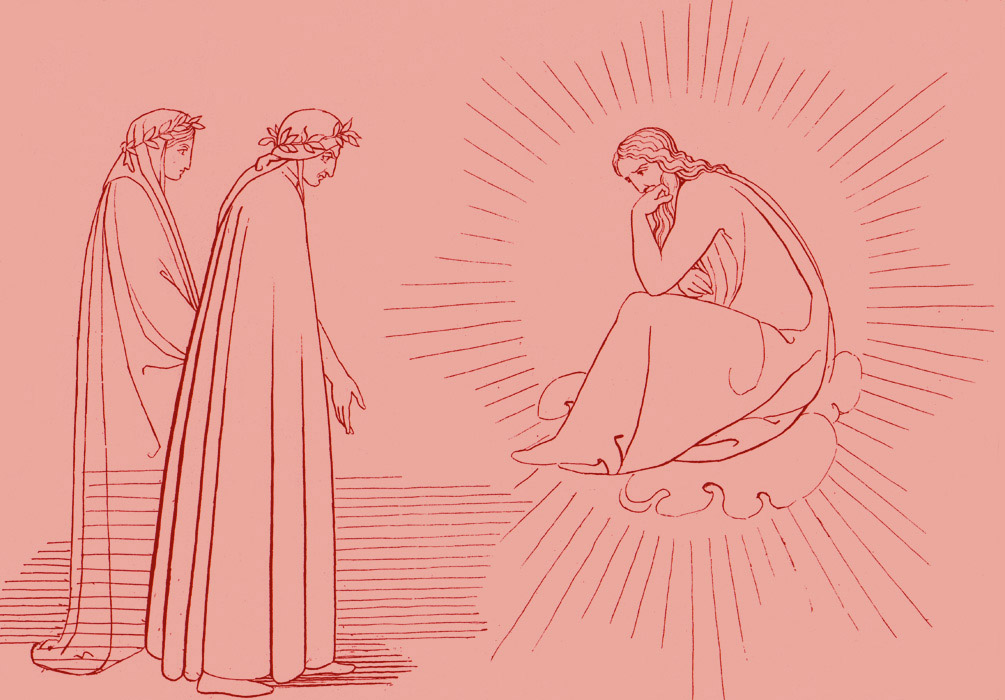

As you might assume, Dante Alighieri’s name would come up often in the course of my ugly year of research on the Via Francigena. He was, after all, resigned to walk to the same trail in part during his own exile over 700 years ago. Finding myself skimming through an old copy of his Paradiso (those of us with graduate degrees in Italian are legally obligated to do this every few months), I came upon the following warning which Dante frames as being recited to the Pilgrim by his great-great-grandfather, Cacciaguida:

You shall leave everything you love most dearly:

this is the arrow that the bow of exile

shoots first. You are to know the bitter tasteof others’ bread, how salt it is, and know

how hard a path it is for one who goes

descending and ascending others’ stairs.

(Paradiso, 17th Canto, 55-60, trans. Mandelbaum)

Stripped of his autonomy, banished from his home, and forced into a life dependent upon the charity of others, Dante’s real-life pilgrimage was marked by pain and indignity. Mine, on the other hand, will be soaked through with beauty and booze and maybe even a few good times!

And yet, how I’ve struggled to truly process that passage for the last few years.

Unlike the poet’s exile, mine is largely self-imposed, and yet I think the emotion I’ve gleaned from his words somehow still taps into the shame and anguish he suffered in leaving his own fate tied to the will of others.

Not bad, Alighieri.

Recently, though, and especially since this unsolicited act of kindness, I’ve begun to think that perhaps the bitter taste Dante describes should be attributed as much to his own pride than to the circumstance behind it.

We live in a society that can afford to feed our poor, and yet as we do so, we shame them as freeloaders and label them as people without value. They’re expected to accept alms quietly, head bowed, with the understanding that such aid is temporary, only until they’re back on their feet and ready to contribute to society once again. This is cruel, of course, but perhaps it’s also short-sighted.

“I

never visited your lands; but can

there be a place in all of Europe wherethey are not celebrated? Such renown

honors your house, acclaims your lords and lands—even if one has yet to journey there.And so may I complete my climb, I swear

to you: your honored house still claims the prize—

the glory of the purse and of the sword.”

(Purgatory, 8th Canto, 121–129)

For all their accomplishments in life as soldiers and dancers and whatever the fuck else they did with their nobility, the Malaspina Family still remains most famous for supporting Dante during his time of need, earning themselves the title of “honored house” that has endured so many centuries later. But more than simply currying favor in the author’s eyes and securing their family such lasting acclaim, couldn’t it be argued that their generosity, inasmuch as it allowed The Guy to write his fucking book in peace, quite directly benefited all of humanity?

I’m not trying to say that this is what my friends are doing here. At best, their donation bought me plenty of shelter and a few fancy amari I’ll end up flushing down the toilet; at worst, it will find me flattened on the side of some ancient highway. I’m just saying that, more than the ever-diminishing euros their collective dollars will afford me, their gift, and the ensuing anguish that it brings, is forcing me to think about “charity”—and the potential power of this trip—a little differently. And for that I’ll forever be grateful.

With this in mind, to those other generous souls who have been asking me how they might contribute, or to those with the means who find themselves reading along joyfully as I flop upon my face, a proposition:

If you’d still like to offer some cashbucks to go toward feeding me and fueling this blog, you can do so HERE. I promise not to complain. And, if you’re comfortable with it, I’d like to spread that help around a bit by pledging half of all forthcoming contributions to Freedom For Immigrants.

Based in Oakland, this non-profit organization aims to end the detention of humans all over the globe simply due to their immigration status, to bring home those who suffer in exile for reasons beyond their control, and to shed light on these struggles. It’s work that stands as a reminder of how fortunate I am to be able to go on this pilgrimage freely and electively, and, to my addled mind, has never been needed more than it is right now.

With great despair and eternal contrition,

Eric Millman